Building an AI Ops Agent

Above: The agent in action: diagnosing a 500 error and patching TypeScript code in real-time.

This post documents my journey building a proof-of-concept framework designed to handle common distributed systems tasks: from analyzing logs to shipping code fixes.

The code associated with this post may be found here: https://github.com/tonyfosterdev/agent-ops-1

Why Operations?

I chose to build this in the operations domain for a simple reason: it’s what I know.

I’ve spent years in architecture and team leadership, and Ops provides the ideal playground for agents. It has clear success criteria (is the site up?), tangible outputs (logs, metrics), and enough complexity to really test an AI’s reasoning capabilities. Plus, if we can automate the mundane debugging, that’s a win for everyone.

The Playground: “Agentic Bookstore”

To test an Ops agent, you need something to operate on. I couldn’t exactly unleash this on a production environment, so I built the Agentic Bookstore.

It’s a distributed application designed specifically to be broken. It mimics a real microservices environment with enough “messiness” (network latency, race conditions, service crashes, etc) to give the agents a challenge.

The Stack

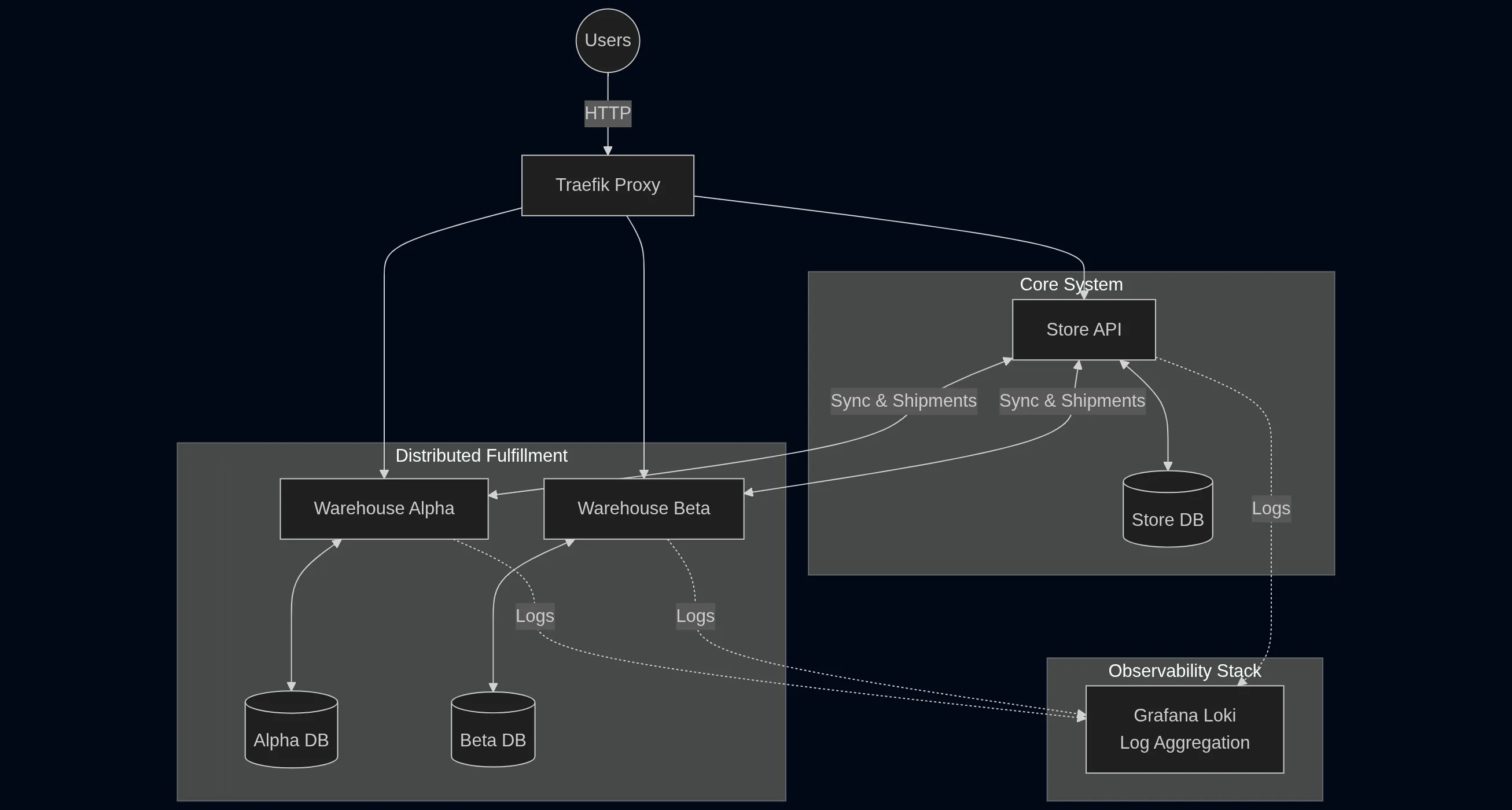

I kept the architecture modern but familiar:

Services: Store and Warehouse APIs built with TypeScript and Koa.

Infrastructure: Docker Compose, Traefik for routing, and PostgreSQL.

Observability: This is critical. To fix things, the agent needs eyes. I used Pino for structured JSON logging and Grafana Loki for aggregation.

The Agent Architecture

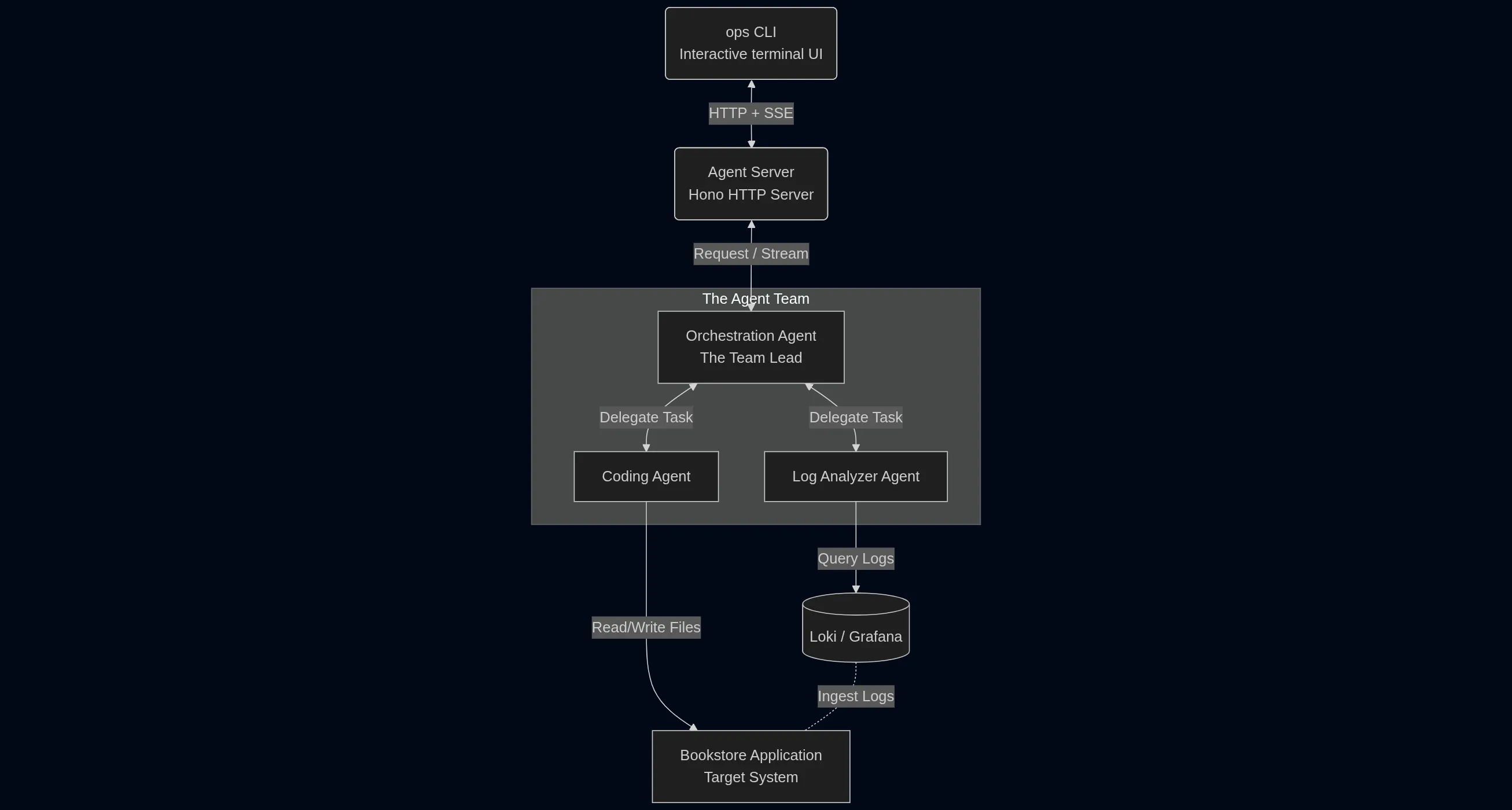

I intentionally avoided a monolithic ‘God Mode’ pattern. Instead, I adopted a Multi-Agent Architecture to enforce a strict separation of concerns. This modular approach isolates failure domains, making the system easier to debug, and prevents context window pollution by keeping prompt contexts focused on specific tasks. The backend runs as a standard HTTP service (using Hono), interacting with the operator through a rich CLI interface (using Ink).

The Agents

Orchestration Agent: The team lead. It takes my request, figures out what needs to be done, and delegates tasks.

Log Analyzer Agent: The detective. It knows how to write LogQL queries, filter noise in Loki, and spot anomalies.

Coding Agent: The engineer. It has file system access to read code, search directories, and write patches.

I chose Claude and the Vercel AI SDK as they’re well known for their developer ergonomics for streaming results back to the client.

Putting It to the Test

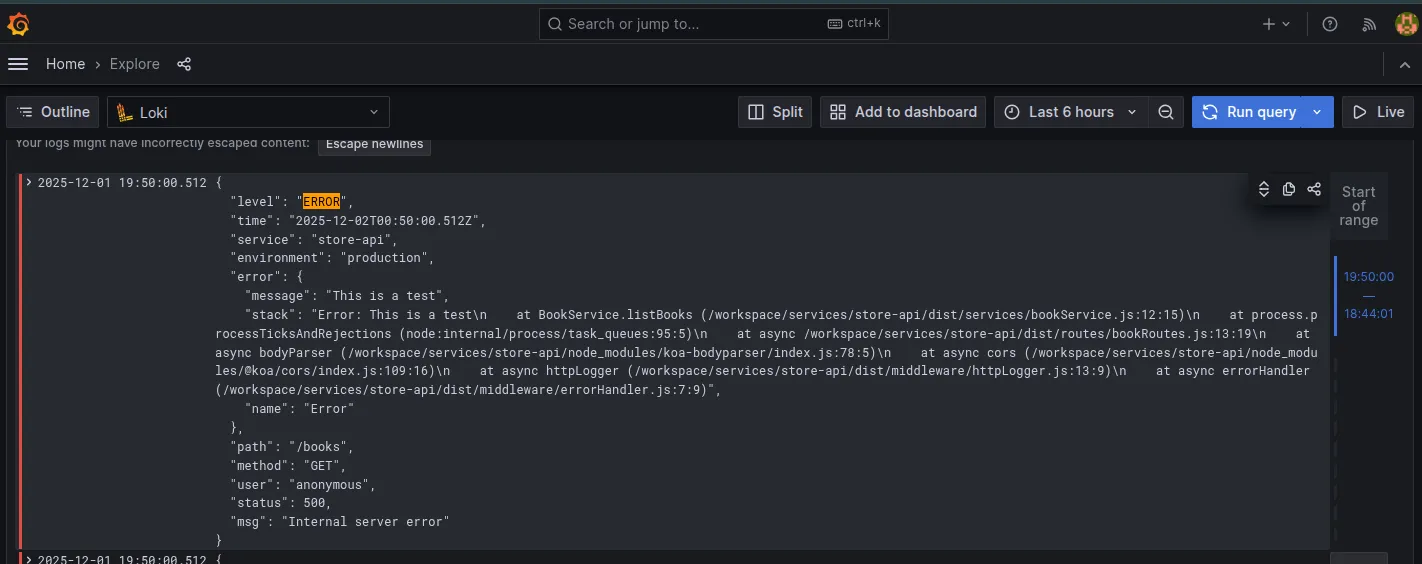

To validate this, I intentionally broke the API. I introduced a bug causing persistent HTTP 500 errors. Then, I gave the Orchestrator a simple prompt: “Can you lookup what’s causing the HTTP 500 error from the store-api book path? Once you find it, please apply a fix.”

Here is what happened:

-

The Orchestrator saw from the prompt that an investigation of logs was warranted and deployed the Log Analyzer.

-

The Log Analyzer queried Loki, found the stack trace, and pointed out the location of the error to a specific TypeScript file.

-

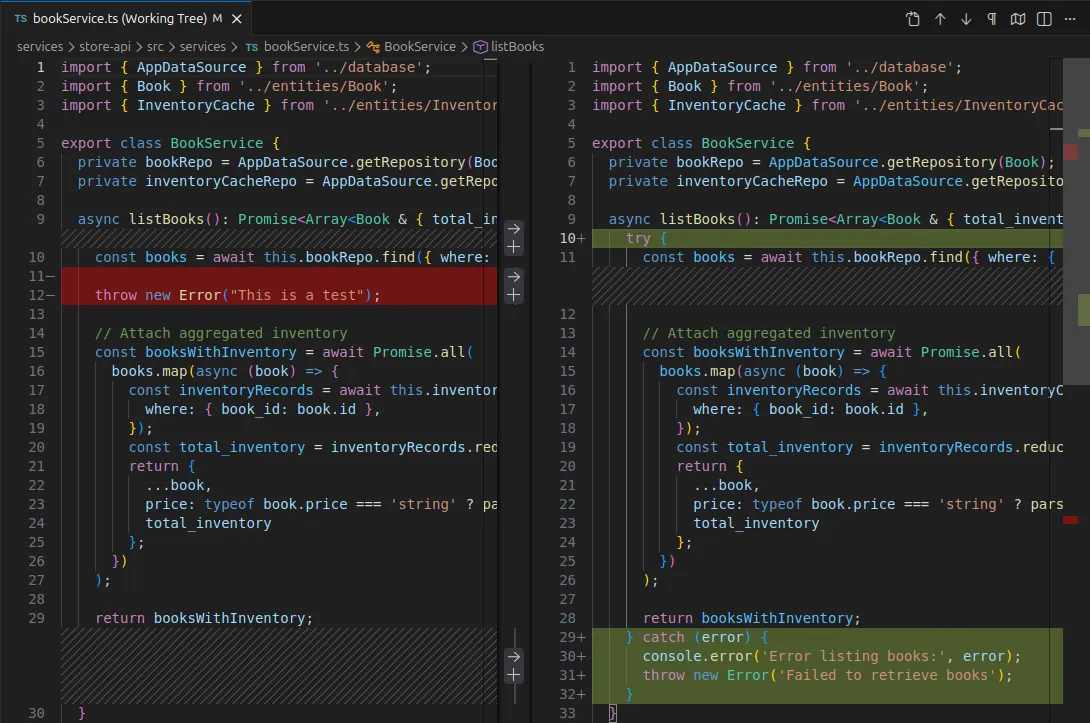

The Orchestrator handed that context to the Coding Agent.

-

The Coding Agent read the file, found the logic error, wrote a fix, and saved it.

- I manually bounced the service, and the errors stopped (a manual friction point I plan to automate soon).

The system went from “broken” to “fixed” with zero human code intervention (aside from me bouncing the service, which is on my list to automate later!).

Reflections & The Path Forward

This proof-of-concept proved that implementing a multi agent architecture with Vercel AI SDK and Hono has promise. However, there are still plenty of challenges to tackle to make this system truly solid:

1. Agent Architecture

While the multi-agent pattern offers cleaner separation of concerns, it incurs distinct costs in latency and token consumption. It is not clear if there are enough gains in reliability to justify this overhead compared to a single, well-prompted agent. Determining this would require a rigorous side-by-side analysis comparing success rates, speed, and cost against a monolithic baseline to confirm if the added architectural complexity is truly warranted.

2. Agent Observability

Right now, it’s hard to see why an agent made a specific decision.

The Goal: I want to implement “Chain of Thought” observability. We need to be able to trace the agent’s reasoning path just as easily as we trace a web request.

3. Measuring Effectiveness

It can fix simple contrived bugs, but can we fix more complex bugs?

The Goal: I need to build a testing framework that measures the agent’s effectiveness against a suite of different failure scenarios, ensuring it doesn’t regress as I tweak the prompts.

4. Enterprise Grade Security

The current setup uses a fairly contrived security model appropriate for a sandbox.

The Goal: Moving forward, this needs to adopt enterprise-grade security practices (proper secrets management and strict sandboxing) rather than just relying on local environment trust.

5. Proactive vs. Reactive

Currently, I have to ask the agent to fix things.

The Goal: True “Agent Ops” should be proactive. I plan to hook this up to alert webhooks so the agent wakes up and investigates the moment an alert fires.

Conclusion

Building the Agentic Bookstore and its digital caretakers was a blast. While we aren’t ready to hand over the keys to the kingdom just yet, the combination of specialized agents and good observability is a powerful pattern.

I plan to address some of the open areas of concern in future posts.

If you want to poke around the code or try breaking the bookstore yourself, check out the repository on GitHub.